Out: Personas. In: Archetypes.

When I was first getting started in UX writing, one of the things that stood out to me was the use of personas. Of course, coming from content writing and editing, writing for a specific target audience was nothing new to me, but the concept of the persona was.

This was the era of clever microcopy and the realization that products could have a “big personality” (read more about that here), and in almost every client conversation, we ended up talking about both the user persona and the product persona (i.e., the persona of the product).

I remember working with one big company that shared a multi-slide presentation outlining at least five user personas in detail, including the stay-at-home mom, her executive husband, their daughter who was studying art at an urban college, the tween son who loved video games, and so on. Then I was tasked with coming up with a persona for the product (I don’t remember the details, but I think we came up with something like a chatty, bubbly executive assistant) and creating my own set of slides about its looks, how it would sound when it spoke, how it would act at a bar, and so on.

In the years since, I’ve ditched personas, especially for products, in favor of archetypes. Here’s why:

1. Personas are made up.

No matter how much detail you put into a persona, it’s still going to be a flat character that you (or someone else) invented. Personas are usually based on demographics, not user research, and they can’t even begin to cover the breadth and depth of the actual human users using your product.

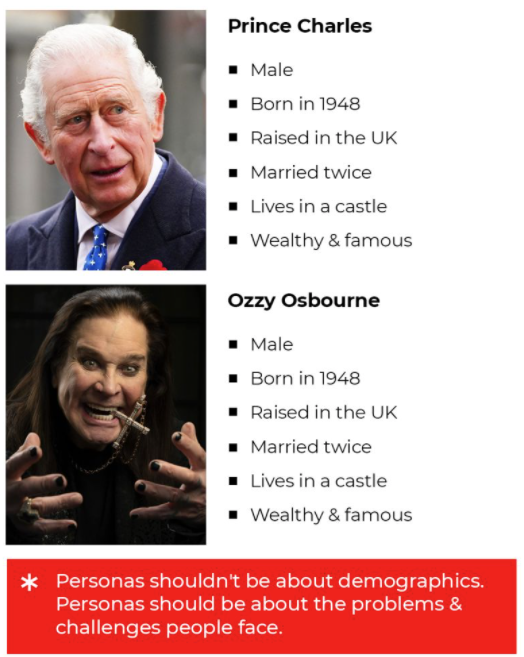

Take the famous example of King Charles (Prince Charles at the time this was created) versus Ozzy Osbourne:

(Taken from Twitter; be sure to read through some of the replies!)

If you create your persona based on demographics, you could easily end up with either a British monarch or a heavy metal artist, which has nothing to do with how the person actually uses the product.

2. Personas are full of bias.

If you tell me “a woman in her 30s,” I’m automatically going to think of someone like myself or most of my friends: a white, young professional woman who lives in a city and works in tech. That’s part of being human—our minds go to what’s familiar, which, in this case, often looks like ourselves and the people around us or like a stereotype we’ve internalized.

That example I mentioned above alone should make you pause: Stay-at-home mom and big-shot husband? It looks like a TV family from the 1950s (with the addition of video games), which keeps our perspective super narrow and puts us more at risk of creating products that aren’t inclusive or accessible.

(Here’s a great article about how personas can stand in the way of user-centric design.)

3. Creating personas is a waste of time.

Every time I’ve had to create a product persona, I’ve felt a little as if I’m writing a novel. I love writing (duh), but—contrary to what I perhaps thought when I was in middle school—I don’t think a novel is in my future. Writing out all of the (mostly demographic) characteristics of the persona often felt like a lot of work, with little reward. And by reward, I mean: it didn’t help me write any better. Creating this elaborate character for my product to guide how it would “speak” didn’t actually make the “speaking” part any easier or better.

Good writers can write in lots of voices and tones—they don’t need a fully developed persona in order to get into the right mindset.

All of that led me to abandon personas in favor of something else: archetypes.

An archetype is a pattern, model, or framework. Archetypes are often used in the context of brands (see the twelve brand archetypes), and at MeravWrites, we’ve developed our set of archetypes—six, not twelve—that we use as frameworks for the personality and voice of the products we’re writing for.

Here are the archetypes we use at MeravWrites:

The Expert – The expert is a product that guides you and provides all the information you need to do certain activities.

Example: An app for learning a new skill, such as a languageThe Coach – The coach represents a product that cheers you on and encourages you.

Example: A workout appThe Enabler – The enabler is a product that gives you the power to do something that may have otherwise seemed out of reach on your own.

Example: A platform for getting legal documents notarizedThe Caretaker – The caretaker nurtures and supports you.

Example: A healthcare app, such as a diabetes-management app

The Assistant – The assistant helps you do something.

Example: Project management software or a bot that helps you submit a request

The Robot – The robot is a product that does something for you in an autonomous, techy, maybe even geeky way.

Example: An AI assistant

When my team and I work on products, we usually define both a primary and a secondary archetype since a lot of product–user relationships don’t fall squarely in just one category.

While archetypes, like personas, can involve bias and stereotypes, what I like about them is that they provide a more general framework to define the relationship between a product and its users (or a brand and its customers). This helps really focus on user pain points and the solutions the product offers, rather than just demographics. In fact, with archetypes, it’s easier to imagine a range of characteristics—for example, it’s easy to think of different types of coaches, of different genders and with different styles, yet who still fit the bill of “cheering you on.”

As a writer, I can take an archetype and run with it, instead of constantly having to check myself on things like, “Wait, would a 50-year-old man say something like this?” Archetypes give me much more freedom when I’m writing and ability to get into the right headspace with regard to the users I’m writing for.

Looking to partner with writers who will identify the right archetype(s) for your product and write a delightful experience? Get in touch!